Status quo: more of the same

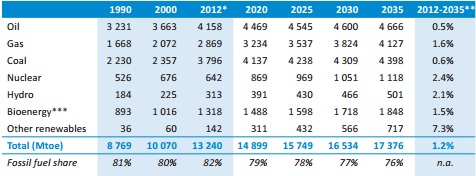

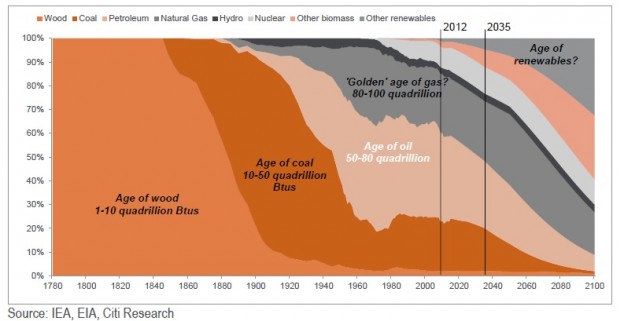

Energy sector is not widely considered to be the sector undergoing any significant changes. Oil, gas, and coal demand are all expected to grow steadily over the next 20 years (IAE forecasts below). Renewables, while growing faster than sector average, leave the fossil fuel market share drop from about 80% at present to 76% by 2035. This ‘more of the same’ scenario is the default view of most of the players in the industry.

World primary energy demand by fuel, IEA, 2014

Yet energy industry is experiencing one of the most significant structural shifts in its history that when viewed in 20 years from now may have a cumulative impact on our lives next only to the impact the adoption of information technologies is having today.

What does it take for a new energy source to change things upside down? It is always about two things – available capacity and cost. Solar energy looks favorable on both.

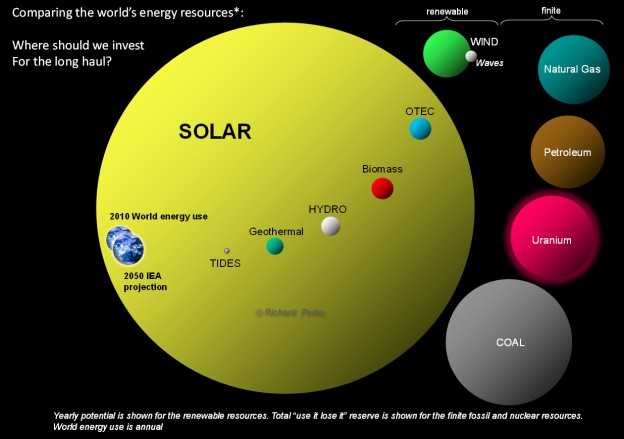

Solar available capacity: unlimited

Over 1 hour the Sun gives our planet as much solar energy as the global economy consumes over 1 year (see illustration below). This is 8,760x more than the global economy uses. If you make adjustments for average cloudiness, proportion of the Earth surface covered by water, efficiency of solar energy conversion technologies, etc you are still left with the gap of couple of orders of magnitude. Thus, for all practical purposes solar capacity is virtually unlimited, making solar a candidate for the ultimate “fuel”. (We may require material progress on fusion in a few centuries, but for now solar is enough).

Note, that unlike fossil fuels, solar is “distributed” much more uniformly across the planet. While “harvesting” for solar in Middle East is still more productive than in Germany, it does not mean it is not productive in Germany at all.

Source: Richard Perez

Solar energy cost: the miracles of compounding

“The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest”

Albert Einstein

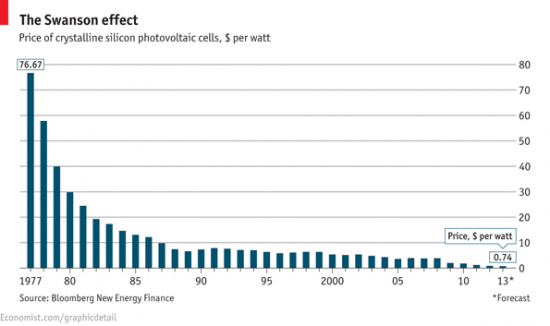

Costs of new technologies typically drop exponentially, and when it goes on for a while – miracles happen. Think Moore’s law in computing hardware. Similar developments happen in PV industry. Over the last 50 years production costs of solar photovoltaic cells went down 100x.

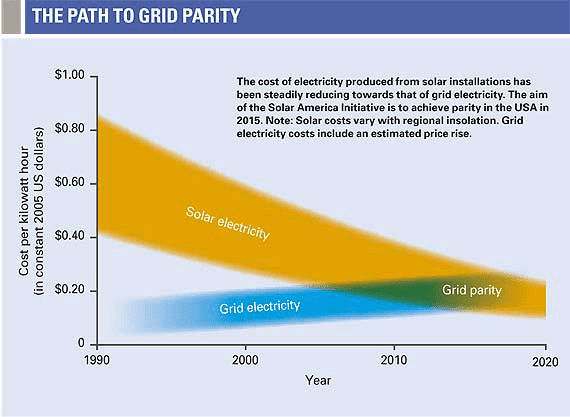

It is easier though to think about costs in terms of implied electricity price and its relation to prevailing market price. Current PV costs (<1$/W of capacity) imply electricity prices comparable to grid prices in many parts of the world. Grid parity has become a reality.

Source: SolarFeeds

Renewable energy as a concept, and solar energy specifically, has been known for decades but its adoption has been slow and limited mainly to the proponents of sustainable green energy. Mainstream remained largely on the sidelines which was hardly surprising. For a new technology to have a truly global impact economic rationale should firmly be in place but until now cost competitiveness has been the missing link preventing widespread adoption of solar. Achieving grid parity is a very recent development likely to significantly speed up adoption of solar. Sustainable/innovative/green/plentiful/etc on their own don’t result in revolutions. Profit does.

Is storage an issue?

To qualify as an ultimate fuel, solar being an intermittent source of energy, needs to address the storage issue. Let us look at the figures.

- The most recent solar power plants in better locations can produce electricity at 6 USc/kWh (unsubsidised). Price tag for unsubsidised wind power is even less (4-5 USc/kWh)

- Tesla produces its best in class open patent batteries at a cost of (estimates vary..) 250 USD/kWh of battery storage capacity. Assume that the battery life is 1000 cycles, and that solar energy produced is 50% / 50% used/stored. Then the implied storage cost is 250 / 1000 * 50% = 12.5 USc/kWh.

- With completion of the Tesla’s battery gigafactory costs are expected to drop below 150USD/kWh of battery storage capacity, driving electricity storage cost to 7.5 USc/kWh.

- Assuming electricity transmission costs of 7 USc/kWh (which is typical today but for such a distributed energy source as solar it is likely to be less), the total (electricity+storage+transmission) is 6 + 12.5 + 7 = 25.5 USc/kWh (20.5 c/kWh with battery gigafactory economics)

- How does that compare to the actual electricity bills? Take UK as an example. Price of electricity in the UK is about 23 USc/kWh (March 2015).

For several years to come storage will not be required at scale as electricity produced from solar will all be consumed at the same time. Economics of real time production is already quite compelling. When solar reaches the stage where pick daytime production is larger than simultaneous consumption (some 20% share of the market?) storage will be massively adopted. The figures above suggest that solar+storage economics is close to par with status quo. And as there is its own version of the Moore’s law in operation in the battery industry by the time storage is required at scale its cost competitiveness is likely to further improve. Thus, storage is not “an issue” but rather “a stage” in the solar adoption process.

Timing

As cost competitiveness for solar energy has become a reality the key question now becomes “how fast does the adoption happen”. Opinions differ enormously.

Image: www.forbes.com Image: www.neftegaz.ru

“Solar will be the plurality of power within 20 years” (2013)

Elon Musk, Tesla CEO

“We will see some rapid changes. Solar power generation will likely increase more than 20 times (by 2040). And yet, even at that very ambitious pace, solar will account for about 2 percent of global electricity supply” (2013)

Rex Tillerson, Exxon Mobil CEO

What does the history teach us? Over the past 200 years energy industry has seen 2 major disruptions (picture below). About 150 years ago coal was taking market share from wood, and 100 years ago oil&gas were taking market share from coal. In both cases the transition (from <10% market share to 80% market share) took about 50 years.

Note that the slope of the curves in the historical part of the picture is much steeper than in the projection part, i.e. IEA/EIA implicitly assume that future transitions will be slower than the historical ones. I think it is more likely to be vice versa.

Demand side developments

It is not only developments on the supply side that are changing the energy landscape. Demand side is undergoing its own structural shifts.

Efficiency of energy use is an important driver. Here is an example. Modern electric LED lightbulbs consume up to 10x less energy than traditional incandescent bulbs. If you haven’t changed your old bulbs yet it makes perfect sense to do so even before the old ones run out. Such replacement would be equivalent of a 10 year investment with only 1 year payback period (first year savings on electricity bills cover the cost of the bulb, and for the next 10+ years of the useful life of the bulb the light portion of electricity bills is reduced 10x times). With lighting accounting for 10-15% of overall electricity consumption, and given that incandescent bulbs are not yet regulated away in many countries, the total impact is significant.

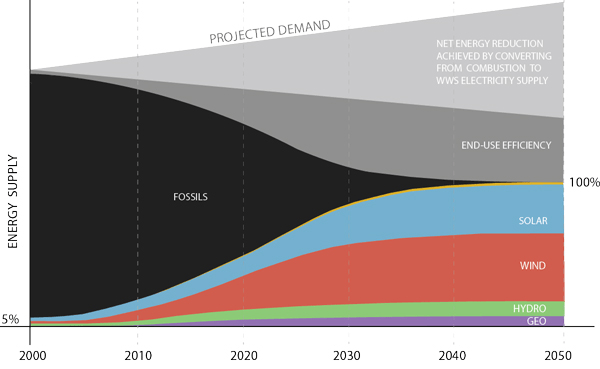

Transition from combustion energy to solar has another important implication. Combustion is not a very efficient energy conversion process. Internal Combustion Engines in our cars have thermal efficiencies of 25-30%, typical large gas turbines that generate electricity have efficiencies of 35-40%, and the most modern combined cycle gas turbines have efficiencies of up to 60%. Thus at least 2/3 of fuel energy contents used in transportation, and about 1/2 in electricity generation, is wasted. On the contrary, if your starting point is solar electricity, the required elements down the chain (battery, electric engine) both have efficiencies of about 90%. It means that if you generate 1 extra energy unit of solar electricity, you can spare 2 energy units of gas. And if you use 1 unit of electricity for transportation, you can spare 3 units of oil. Thus electrification means that there is a structural downward pressure on gross energy demand due to energy conversion inefficiencies elimination.

Is Elon Musk right?

Combining the trends above (adoption of solar, improving efficiencies, and electrification) the ultimate transition picture may look like this:

Source: Scientific American

Take US as an example. In 2014 solar+wind accounted for 5% of the US electricity market. Electricity generated from solar+wind grew 13% y-o-y (with solar more than doubling), and more than 50% of all new capacity added throughout the year was attributed to solar+wind. The last figure should be read with caution as different types of capacity have different utilisation rates, but it is clear that solar+wind takes a much larger share of marginal investments than its current share of the electricity market. It means that solar+wind share of the electricity market is set to grow. If the current growth rate stays the same (which I think is a conservative conjecture) and assuming the market is flat (efficiency gains compensating for market demand growth) then by 2030 solar+wind would account for 35% of the electricity market (which indeed would be a plurality). At the same time fossil fuel capacity will be phasing out. The best fossil fuel facilities will live through their full economic life and be replaced with solar, the others will be replaced prematurely.

Investment implications

Traditional electric utilities with coal and gas fired generation capacity will continue losing market share to solar+wind. The better of the electric incumbents will run their business for cash selectively investing in new opportunities (such as industrial scale solar+wind and storage). As the full transformation cycle will take 20-30 years cash generated during the phasing out stage will burn pockets (effective running a not a going concern business for cash is a rare corporate quality). Reinvestment opportunities though are naturally limited as solar is a distributed resource that doesn’t necessarily require participation of industrial giants (with a solar panel on the rooftop the electric companies of the future are you and your neighbour). Low P/CF multiples may indicated attractive investment opportunities provided CF translates into FCF.

Oil incumbents have many common problems with their colleagues in electricity sector. Electrification of transportation does to oil what solarisation does to electricity. While the cost of ownership of fully electric cars is yet to match that of gasoline/diesel cars (the cost of batteries needs to fall further), modern hybrid electric vehicles are cost competitive at almost any oil price due to supreme fuel efficiency (75 Miles-Per-Gallon for modern hybrids vs. 25 MPG for existing fleet). Electrification of the powertrain is also the only way to capture the full potential of regenerative braking (as you need batteries or capacitors to store the energy released from the vehicle motion). Existing cost competitive hybrid technology alone is enough to reduce oil usage in transportation by up to 3x per vehicle over the next 15-20 years. With respect to the impact it will have on total oil demand adoption of hybrids is likely to outweigh the effect of gradual growth of motor fleet.

Facing a similar structurally declining trend, in one important aspect the position of oil incumbents is worse than that of their electric industry peers. Unlike electricity generators oil companies can not stop investing and sit on free cash flow. One of the characteristic features of the oil industry is natural decline rate of oil production. If oil company stops investing (drilling new wells) its production would fall about 7% y-o-y as pressure in the existing reservoirs naturally declines over time. You need to keep spending to keep production flat. Thus the prospect of the wall of free cash flow during phasing out stage is not what we should expect in the oil sector.

Major oil companies currently yield about 5% which means their investors expect to generate another 5% through trend EPS growth. I don’t think this is realistic. We are a few years away from the point at which oil demand starts structurally shrinking. When do you want to be an equity investor in a declining business to generate acceptable returns? Only when the initial yield is in double digit range. We are far from that point.

The damage done through the oil price (that almost halved over the past few months) impacted the financials, but not the market share of oil companies on the overall energy market. Structurally declining oil volumes is a soon to come many years trend.

New technology / new players are not necessarily the ones to reap the benefits either. If Solar had an owner it would be the largest and the most expensive franchise in the world. But it does not. The new economics of energy is that of a technology industry, rather than a rent sharing industry. Emerging solar industry is naturally deflationary, producing undifferentiated commodity product (whether it’s solar panels or electricity from solar panels), and unable to create brands around its products and services to protect margins. Underlying technology always keeps improving. If you own a patent for a particular 20% solar-to-electricity conversion technology, it doesn’t mean the guy who invents a 25% technology (and stands ready to take your market) works for you.

Look 100 years back. The tech revolutions then were automobile and aviation. Both have fundamentally changed the world. But what happened to capital providers to those industries? US alone had hundreds of automotive startups back then most of which lost fortunes rather than made fortunes. The ultimate winner in the innovation race is the consumer and the general quality of life, rather than providers of capital. As an investor you really need to know well what you are doing if you trying to pick up the winner. Without a doubt it is easier to name the losers than to pick up the winners.

Macro implications stem from currencies to current accounts to politics. Oil-linked currencies will suffer (including the ones formally pegged to USD), current accounts surpluses would shrink. Functionality of the US current account deficit to provide USD liquidity to the rest of the world will be reduced. Certain Dutch diseases will be treated, but some countries will need to find a new place in the global division of labour. Internal political agenda will change in those countries as rent economies and non-rent economies demand different political frameworks.

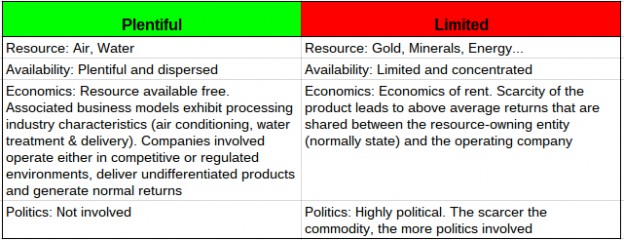

General implications

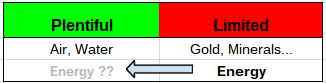

All resources that humankind uses generally fall into 2 categories: plentiful, easily available, and largely free (like air and water), and limited (minerals, energy, etc).

Up until now energy undoubtedly has exhibited the characteristics of the second group. More precisely energy defined the second group. But with the ongoing developments it is likely to drift to the first.

Energy is becoming a boring processing industry, ‘harvesting’ for a plentiful resource and delivering clients an undifferentiated product. Economics of this business will vary from place to place, but ‘rent’ will not be a characteristic feature of the industry any more. The companies involved will be generating return on capital employed in mid-to-high single digit range (similar to stable utility businesses), and the sector will be off the political agenda.

Second order effects

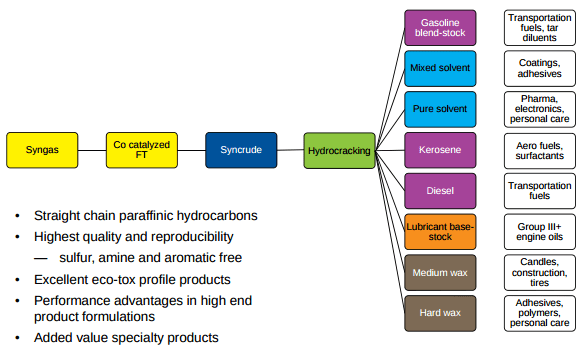

Cheap and abundant energy may resolve some of the seemingly unrelated problems using the existing technology and processes which until now were deemed uneconomic. For example, chemical industry still needs long-chain hydrocarbons for various industrial purposes. How do you permanently and economically address this problem if oil feedstock is only a temporary solution? You can take water, apply electricity to split it into hydrogen and oxygen, then add carbon dioxide (now considered a headache rather than a valuable carbon resource) to produce methane, then you reform it into syngas, that can be converted into a wide variety of chemical products using Fischer-Tropsch process:

Source: Velocys

You start with abundant and free water, abundant and cheap energy, and problematic carbon dioxide to provide for a great variety of chemical products currently sourced from oil. This is a permanent, sustainable, and now becoming economic fix. All of these processes have been known for decades but belonged mostly to the laboratory as cheap energy has been the missing link. But not any more.

Scarcity vs. Abundance = Dystopia vs. Utopia?

With accelerating progress in many fields (energy, manufacturing, information technologies, biotechnologies, etc) it feels like, after all, the humankind is on its way to anti-Malthusian abundance of everything.

vs.

What challenges does such future bring? What will motivate people when you need to do very little to satisfy all principal needs (food, home, etc)? Will everyone be either a scientist or an artist? Will people question the meaning of life even more furiously? Or nothing really changes as people continue to be competitive beings measuring satisfaction from life with the reference to the neighbour as opposed to any absolute thresholds? It remains to be seen.