The prices of electricity, oil, and gas have been interlinked for a long time. Such price connections are often fundamental in nature (energy sources having a common market, energy sources interconnected vertically), and are the basis of some existing business models (gas fired electricity generation, gas to liquids conversion, etc). The ongoing developments in the energy space, primarily elimination of combustion as a marginal technology to produce electricity, will impact some of the price ratios and corresponding business models.

Common market: oil vs. gas

Prices of oil and gas have long been interconnected through a common market: both commodities have been used as raw materials to generate electricity (through combustion process). If oil price was high (relative to gas) people would switch to gas, and vice versa, producing relatively stable relative pricing.

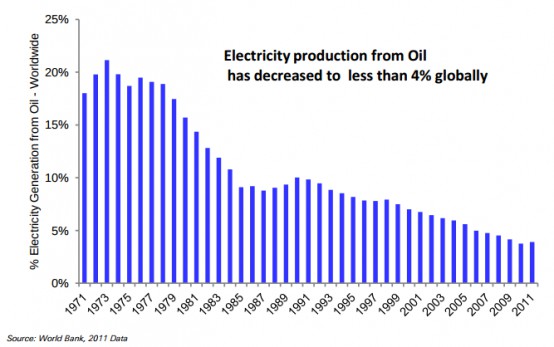

But over the last 30+ years the share of oil in electricity generation mix has reduced from 20% to less than 4% today and continues to fall.

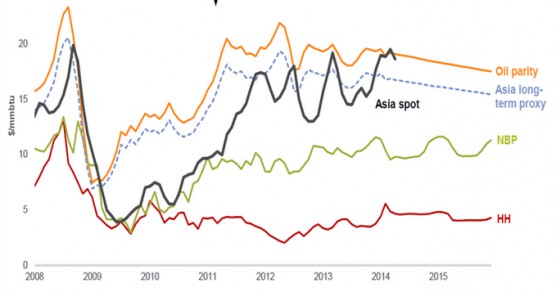

The common market for oil and gas has effectively gone. Today there is little fundamental reason for oil and gas prices to be interrelated, instead the two should be determined by their own supply/demand dynamics. And this is already seen in the market prices (see picture below). The US gas price (Henry Hub) reflecting the successes in the shale gas space unbundled from oil first. Europe where gas spot market (for imported gas) is developing fast is following the lead. Only Asia/Japan exclusively dependent on LNG-imported gas, still the tight market, sticks to traditional oil-linked pricing. Note that LNG prices will always be higher than gas prices in the places with local production, but the right reason for LNG price premium is high capital cost of the technology rather than historical pricing off oil. As global LNG capacity is growing fast we are soon to see the Asian gas market unbundling from the oil price as well (at the levels reflecting LNG economics).

Source: Gaffney, Cline & Associates

Vertical chain: gas vs. electricity (wholesale)

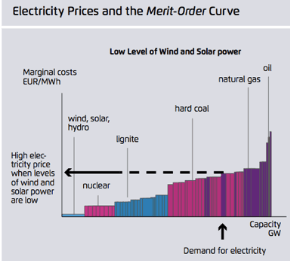

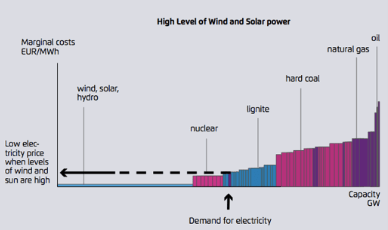

In many electricity markets gas-fired generators produce the marginal quantities of electricity (typical merit order shown below) and set the electricity market price most of the time.

Source: Agora Energiewende

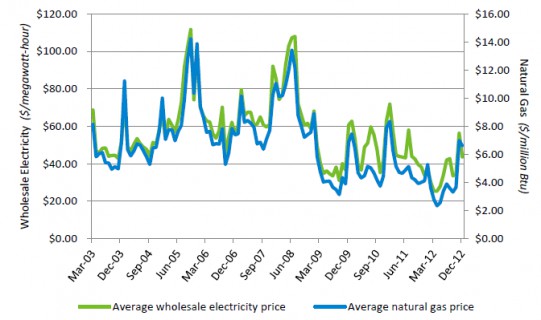

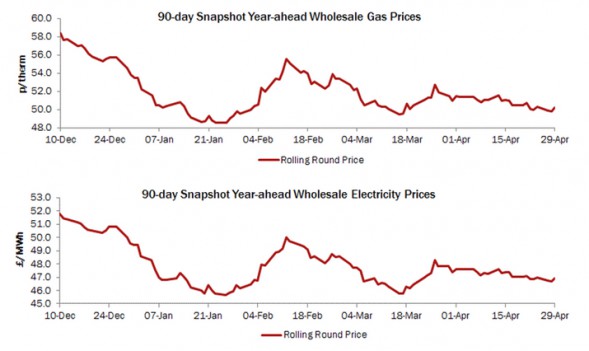

Gas combustion as a physical process has certain characteristics that stipulate the connection between wholesale gas and electricity prices. Modern combined cycle gas turbines (CCGT) have efficiencies of up to 60% (that is 1 unit of energy contained in gas is converted into 0.6 units of energy in the form of electricity). This conversion coefficient is the key factor determining the gas/electricity price ratio. The ratio has been stable (in gas-fired electricity markets) over the years (chart below for US), and current prices on commodity exchanges still show perfect correlation (chart further below for UK).

Source: The Neutron Economy

Source: Utilitywise

NB: Actual gas/electricity price ratios, as inferred from the two charts above, are around 40% (Take the very left data point in the second chart for example: 1therm = 0.1mmBTU = 1/34MWh => gas price of 58p/therm = 0.58*34 = 19.7£/MWh(of gas) => gas/electricity ratio = 19.7/52=38%). The 40% range (rather than 60%) is due to: 1) the spread that gas-fired utilities generate needs to also cover CapEx and OpEx, and 2) not all of the marginal generators are modern CCGT (some are single cycle turbines with lower efficiency). In other words, typically, wholesale electricity price is 2.5x the wholesale gas price (on calorific equivalence basis).

Changing tides for combustion as a price setting technology

The status quo has been this. Gas was selling at whatever the price it was selling (typically priced off oil), gas-fired utilities converted gas into electricity at combustion-specific conversion coefficients, that set the market price of electricity as well as relative gas/electricity prices. But with the recent developments in the alternative energy space gas firing has now been challenged as a marginal technology to generate electricity. Solar and wind have become cost competitive in many markets gradually replacing combustion as a marginal technology (and price setter). As combustion is becoming less competitive, combustion-driven price ratios (discussed above) are losing fundamental grounds.

Effectively with more solar and gas capacity coming upstream causality is changing. In combustion-era market price was a function of gas price and conversion coefficients (more or less physical constants). The market price was an endogenous parameter. Now, with competitive solar and wind, from combustion point of view market price becomes an exogenous parameter challenging the current economics (as per picture below). As input price (of gas) remains the same, and output price is lowered by solar/wind disruptions, the combustion economics is not working any more.

Source: Agora Energiewende

One of the most likely outcomes of such developments will be downward pressure on gas prices. Something that no one cared about before (as whatever the input costs were they were passed through on to the consumers), now will be a major trend for years to come. This pressure will help break the oil/gas price links in the places where it hasn’t happened already (Europe/Asia).

The ultimate future of gas-fired electricity generation is difficult to predict. What will be the end point of putting pressure on gas prices (to allow for adequate spread making gas firing economical)? Combustion as an energy conversion process to generate electricity has relatively low efficiency (which is a physical limitation that can’t be changed). For electricity generation purposes, on calorific basis gas will always need to be priced below 50% of its energy contents. But what if the alternative demand for gas (as a source of carbon in chemistry for example) would stand ready to pay a higher price? Than gas combustion is dead. The other possibility is that cost of gas production goes above of what is needed to stay competitive with solar/wind. Than gas combustion is dead either. These are distant perspectives hard to see from where we are today. Gas firing will certainly continue as long as we have easier targets (like polluting and expensive coal plants), it will likely be losing market share later to solar and wind, it will possibly stay as a balancing electricity provider (competing with batteries), but whether it goes away completely to me is unclear.

Vertical chain: gas vs. electricity (retail)

Let’s look at the gas/electricity price ratios for the ultimate buyers and stick with the UK as an example. Retail price gap in the UK is even higher than 2.5x on the wholesale markets. This is due to much higher volumes of gas consumed by an average household compared to electricity volumes (according to the British regulator Ofgem an average household in the country consumes 3,200 kWh of electricity and 13,500 kWh of gas per year). This is 4.2x more gas. When other costs (other than wholesale gas/electricity costs) are averaged out over those volumes it turns out that overhead costs per 1 unit of gas are so low that retail electricity price is about 3.5x higher than the retail gas price.

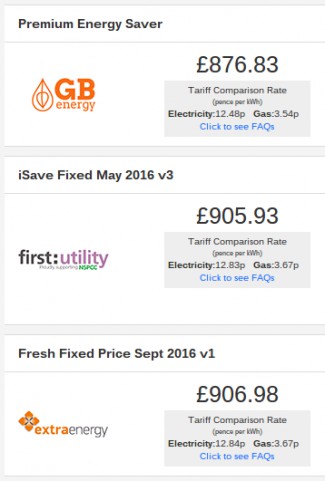

Here is an illustration of what some of the cheapest UK energy providers offer (Gas/electricity price gaps in those examples are 12.48/3.54=3.53x; 12.83/3.67=3.5x):

Source: Energylinx

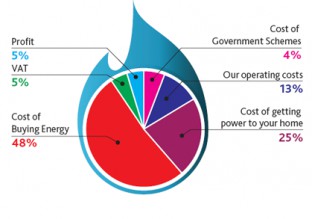

End of combustion era will impact this 3.5x ratio in retail prices in the same direction as the wholesale price gap, but overall implications are more complex. To understand that we need to have a look at the retail energy bill structure (below).

Source: NPower

Wholesale prices of electricity and gas are between one third and one half of the total bill. Consider the following extreme scenario:

- Wholesale electricity price goes as low as ZERO

- Cost of Government scheme (‘green’ levies imposed on electricity) goes away

- Other costs (VAT) correspondingly shrink as well

In such a scenario the retail electricity price goes down by 35%+13%+c2% = c50%, and thus retail gas/electricity price gap shrinks from 3.5x to 1.75x. (On calorific basis) electricity remains much more expensive than gas for home users, no matter how cheaply electricity can be produced and sold on the wholesale market. It has important implications for home energy.

Home energy: the case for home CHP

In those parts of the world where there is no central heating, people at home typically use electricity for lighting and appliances, and gas for heating (via gas fired boilers producing heat). Modern gas fired boilers are very efficient (90%+). There are also electric boilers around (90%+ efficient too), but people typically choose gas boilers as gas is 3.5x cheaper. (NB: As thermal efficiencies for the two types of the boilers are similar, feedstock price comparison on calorific basis is the appropriate one).

As we have seen no matter what the wholesale electricity price is, home electricity price will always be a multiple of home gas price: 3.5x currently and always (structurally) above 1.75x. Alternative energy revolution or not, in the current layout gas is cheaper to heat homes than electricity.

There are technologies and business models targeting to exploit this price difference. As the multiple of 3.5x is a result of a) structurally low efficiency of combustion process, and b) higher unit cost of electricity delivery (compared to gas), what if there was a way to use lower cost gas to produce higher cost electricity without wasting the combustion byproducts (heat)? This idea is not new. Combined Heat and Power (CHP) systems are a proven concept on a large scale, but miniaturization of the technology so far has been unsuccessful (to utilise difficult to transport heat it needs to be local, and to be local it needs to be small). The home solutions proposed so far either suggested you would need to have a combustion engine in your house (as integral part of your CHP boiler) which is somewhat noisy and costly, or relied on costly fuel cell technology. But newly emerging solutions are now available at a price lower than the resultant cumulative energy bill savings. Effectively in the current price environment the boiler pays for itself.

Source: Flowgroup

What if the environment changes? What needs to happen for gas to stop being a preferable home feedstock, and micro-CHP a preferable home energy technology?

- First, decline in the price of electricity (as an alternative feedstock and a candidate to replace gas at home completely) is needed. In other words the 2.5x gas/electricity price gap on the wholesale market needs to become less than 1x. This is structurally not possible in the era of combustion-based electricity, but theoretically possible in the era of solar/wind-based electricity. How far are we from that point? The cheapest solar energy available today is at 6USc/kWh, the best wind is available at 4USc/kWh, and the best gas is as low as 1USc/kWh! (US’ Henry Hub quoted price of below 3USD/mmBTU * 3.4mmBTU/1MWh). In other words solar and wind are successfully challenging gas-fired electricity already today, but not gas itself. Wind is cheaper but is a more mature technology, solar is more expensive but has more potential. There is a long way to go. The gap may hold even in 2050.

- Second, as we have seen cheap electricity is not enough. Cost of electricity delivery (per 1 unit of electricity) is higher than that of gas, and as things stand is prohibitive (for electricity to be more attractive than gas) on its own. But delivery cost is an endogenous parameter here. If and when electricity becomes cheaper than gas (at production point), people will want more of electricity, and electricity delivery costs averaged over much higher volumes will drop. If the right things happen on the cost of production side delivery costs will follow. Gas and electricity would reverse positions, both in terms of retail price and (household) volumes.

Wholesale electricity price below 1USc/kWh is certainly a distant if at all achievable perspective. It secures some market for gas even in the era of post-combustion centralised electricity, and should be encouraging for micro-CHP solution providers. And we haven’t touched storage yet.

High grade energy vs. low grade energy

Not all of the energy forms are created equal. Depending on the ease at which one form of the energy can be converted into another one people distinguish high grade and low grade energy. In the combustion age high grade electricity (desirable and transportable product) is contrasted to low grade heat (unwanted byproduct of combustion difficult to utilise at electricity generation facilities).

Ongoing elimination of combustion as a price setting technology will redefine the terms. In the post combustion era heat is only produced where it is needed (homes), and while technically still meeting the definition, it does not any no longer feel any lower grade than electricity. Just two different markets. Two different needs. But in the world dominated by solar and wind there will be two types of electricity – intermittent and untimely (solar, wind), and scheduled and timely (traditional gas-fired, CSP, batteries). Timely electricity is the new meaning of high grade energy, as opposed to consume-as-you-generate solar and wind (new low grade energy). These two types of energy will have a different price and the markets (and regulators) will find the way to price it properly.

In this regard, costs of gas-fired electricity (timely and scheduled) should not only be compared to the costs of solar/wind electricity (intermittent), but also to the cost of batteries. In a way, gas feedstock also serves a function of a battery, though in a combustion world there was no need to recognise this angle as all other feedstocks possessed the same feature. To assess the full impact of electricity storage incorporation requires a separate exercise, but it is clear that the cost of storage will be pushing the retail electricity price (vs. gas) upwards supporting the case for micro-CHP home solutions.

Summary

- Many business models in the energy industry are built on certain price ratios between different energy sources. These price ratios are built on fundamentals, some of which change over time.

- Oil and gas used to have a common marketplace (for electricity generation) and hence were priced with reference to one another. There is no common market any more (oil is now used in transportation and chemistry, while gas is used for electricity and heat generation), and so the price link has already been broken (US), is being broken (Europe), and yet to be broken (Asia).

- Gas and solar/wind currently have a commonplace (for electricity generation). As solar/wind have now become competitive and getting even cheaper due to continuous improvements in technology, this common market may go. Electricity will be dominated by solar/wind, while gas will continue as a feedstock for heat generation and chemistry.

- Even after gas-firing to generate electricity fades away, for a certain period of time electricity will continue to be more expensive than gas. This guarantees gas a market (for heat), and home energy solutions are likely to be dominated by micro-CHP.

- When electricity becomes cheaper than gas, gas loses its market (for heat) to electricity, and micro-CHP go away. Home energy will be 100% electrified. But this is at least several decades from now.

- Upcoming domination of solar/wind is giving rise to new interpretation of high grade energy (timely electricity) and low grade energy (untimely electricity). The difference between the two (the storage gap) brings about some new price connections in the energy space.