Energy systems of the near future, responding to economic signals, are set to become more local in comparison with today’s paradigm of centralised energy production:

- Solar, an exception to the trend, will largely migrate from the enthusiasts’ rooftops to centralized industrial locations.

- Large-scale electricity generation based on gas combustion, now one of the cores of the centralised power production, is challenged by more distributed solar/wind and is set to be losing market share.

- Small-scale electricity generation will enter our homes (via new enabling technology) complementing traditional (heat producing) gas boilers.

- Gas-based chemistry is set to move small scale.

- Whatever comes to replace gas-based chemistry (artificial photosynthesis?) would come small scale as well.

Rooftop solar goes industrial scale

A typical image that comes to mind as an illustration of the new developing energy systems is this:

Source: Inhabitat.com

Locally produced, distributed power ‘harvested’ from the sun. Developments in the alternative energy have indeed followed this path (rooftop solar panels installed by the enthusiasts) but only up to the point when alternative energy has become competitive, at which stage it has become clear that the image above, as a representative picture of a typical future energy system, is mostly misleading.

The problem with rooftop solar is that 1) there is not enough rooftops around, 2) economics of industrial scale solar is better:

1) Capacity.

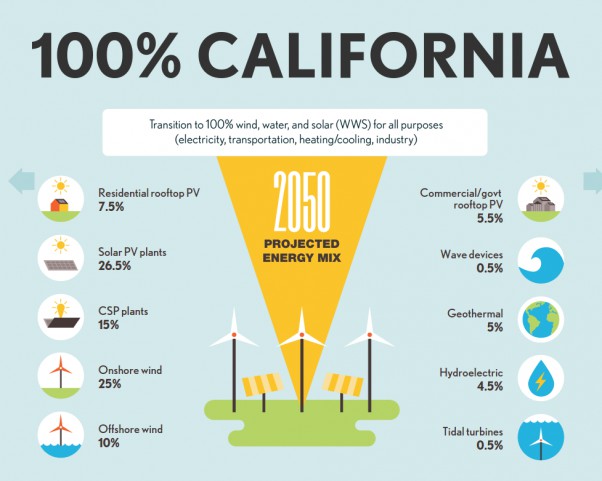

In a recent technical feasibility study, a group of researchers established how a 100% renewable energy future can look like for the US. Here is an illustration for California:

Rooftop solar in this layout is only 7.5+5.5=13%. In most of the other states rooftop solar accounts for no more than 10-15%. Which means that 85%+ of the renewable power produced in the future will continue to be centralised.

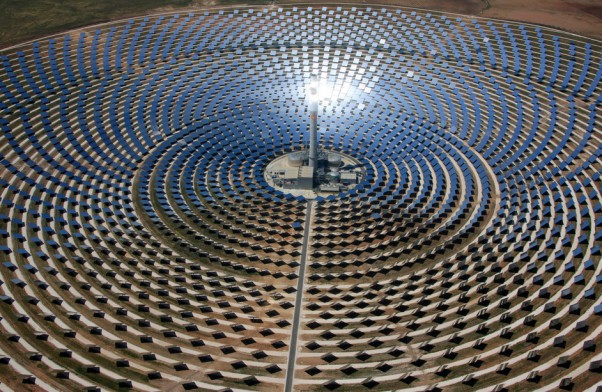

So the right images to bear in mind are these:

PV power plant (image source)

CSP power plant (image source)

Wind power plant (image source)

2) Economics.

85%+ (proportion of centralised energy) can be anywhere between 85% and 100%. Depending on economics. The pros and cons of rooftop solar are these:

Pros:

- While installing PV panels at the rooftop the homeowner avoids/reduces a grid charge.

Cons:

- With small scale installations, like that of rooftop solar, the costs are structurally higher than for industrial scale facilities, as overhead costs (labour, AC/DC inverter, home battery) spread over small installed capacity are high.

What outweighs what is unclear as the right answer may be different for different locations.

Thus, here is what we know:

- From the feasibility study (referred above) we know that up to 15% of the power can technically be produced locally off the rooftop.

- In some locations rooftop solar is more economic than the status quo (grid provided electricity) already today. The number of such locations will continue to increase over time.

- What is unclear though is whether in the situations when rooftop solar is preferred to the grid, rooftop solar is the best alternative possible. It may be that industrial solar would still dominate rooftop solar (while both would dominate the grid).

That you can produce up to 15% power off the rooftops does not mean you should.

Feasibility study vs. actual developments

Not only the technical feasibility study points at the conclusion that industrial scale generation will continue to dominate the power industry after the ongoing transformations, but the actual initial developments as well.

Here is a few observations:

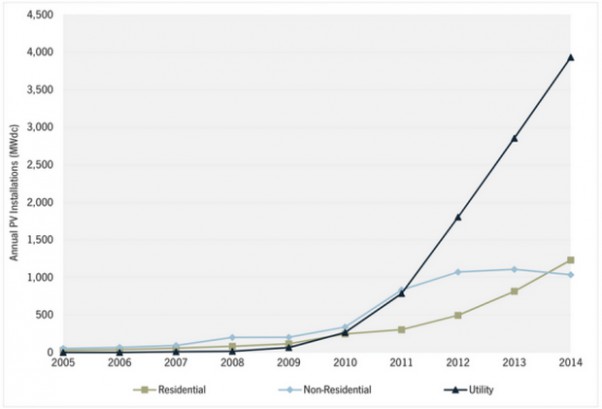

- On the solar panels side, utilities are quickly catching up on solar installations, moving from a laggard position in the early adopter times (pre 2010), to being the core source of demand. As per the chart below 60%+ of all new PV installations in 2014 (in the US) was utilities’ demand.

Source: Cleantechnica

- On the storage side (which naturally complements intermittent solar), Elon Musk at the recent annual Tesla shareholders meeting, while commenting on the new Tesla home storage product noted: “We expect most of our activities to be with the Powerpack, not the Powerwall. So it’s probably 80 percent, maybe more than that, of our total energy sales that are likely to be at the Powerpack level to utilities and to large industrial customers”

The theoretical conclusions agree with actual developments.

The exact estimation of the share of (distributed) rooftop power is a subtle issue, and is not the purpose of this exercise.

Combustion devices enter homes

Whether rooftop solar is 0% or 15%, 85%+ of power stays centralised which means that the central grid does not go anywhere. The grid’s structure will probably change: as the network of solar & wind power plants will be more distributed than the current network of combustion-based generation assets, the grid will need less long distance/high voltage transmission links and more local distribution links. But the grid stays in place, with some important implications that follow.

In a note on relative prices of different energy sources, I shared my views on why in the electricity markets with the following characteristics:

a) combustion-dominated generation

b) centralised generation

i.e. in the typical markets of today, the gap between electricity and gas retail prices (calculated on calorific equivalence basis) is as high as 3x+:

- Wholesale price: combustion inefficiency. Efficiency of (gas) combustion as an electricity generating process is structurally low (less than 50-60%), which requires wholesale electricity price to be 2x+ that of wholesale gas price.

- Delivery (unit) costs: volume driven. A typical household (in most places other than Russia and Northern Europe), using gas to generate home heat and electricity to feed the appliances, consumes much higher volumes of gas compared to electricity (measured in common units). As such, delivery costs and other overhead costs, spread over lower electricity volumes drive the electricity/gas retail price ratio even higher (3x+)

Combustion-dominated electricity generation is being successfully challenged by solar and wind, thus ‘combustion inefficiency’ (in electricity production) will not be a valid argument one day. But to challenge gas on the electricity market is not as easy as to challenge gas on the heat market. In fact, gas stays hugely competitive as a source of heat:

(***)

- Best gas price is 1USc/kWh (US’ Henry Hub price of 3USD/mmBTU * 3.4mmBTU/1MWh energy conversion coefficient)

- Best gas-fired electricity is 6.1USc/kWh

- Best wind is 4USc/kWh, best solar is 6USc/kWh

- And best storage is 3.4USc/kWh (if you want to compare ‘storable gas’ and ‘storable electricity’, a kind of apple to apple comparison, wind and solar prices need to be adjusted by that amount giving 4+3.4=7.4USc/kWh for wind, and 9.4USc/kWh for solar)

So as the numbers show, while timely solar and wind start challenging gas-fired electricity, gas is very difficult to beat as a source of heat.

As solar and wind stay largely centralised (as established above) using the existing centralised grid, the second argument (on ‘delivery unit costs’) will still hold. As people stick to gas as the most economic source of heat there is a stable, self-reinforcing equilibrium: gas is cheaper than electricity => people use gas in large volumes to generate heat => large volumes of gas make gas delivery costs even cheaper, adding to gas competitive position on the heat market.

The current situation is this:

- Structurally inefficient, large-scale gas-combustion is being challenged by solar and wind on the electricity generation market.

- (Small-scale) gas-combustion stays grossly competitive on the heat market.

- Electricity-over-gas price premium stays in place despite (1)

The combination of (2) and (3) provide for an opportunity. While the large-scale gas combustion business model (burn gas to generate electricity / waste heat by-product) has already seen its better days and soon may be not competitive, there are technological advancements that enhance a still valid small-scale gas combustion business model (burn gas to generate home heat via a traditional gas boiler) to an even better proposition (burn gas to generate home heat / co-generate electricity as a premium by-product).

Moving from large-scale to small-scale gas combustion, switches main product and by-product (from electricity/heat to heat/electricity) making by-product a valuable bonus, rather than an unwanted waste.

There are first propositions on the market exploiting this opportunity, that cost the customer less than the savings (due to (3)) delivered.

Source: FlowGroup

How does the future of gas-combustion look in the age of solar and wind? Small scale, distributed, and long-lived. How long? Until the moment when wholesale electricity price becomes cheaper than wholesale gas price (on calorific equivalence basis), at which point the customers will be incentivised to switch to electricity as a primary energy source to generate home heat (provided the suppliers lower electricity delivery charges reflecting higher electricity volumes). Looking at the figures (***) above, renewable heat “grid parity” moment is probably 10-20 years away, unlike solar/wind electricity “grid parity” that is already today’s reality.

Natural gas as a source of heat

As a schoolboy in Russia, for the first few years in high school you study inorganic chemistry, and later switch to organic chemistry that deals with:

“structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain carbon atoms (C)”.

Specific characteristics of one atom give rise to a whole separate subdiscipline.

“Methane (natural gas’ primary component), CH4, is the simplest organic chemical and simplest hydrocarbon, and molecules can be built up conceptually from it by exchanging up to all 4 hydrogens with carbon or other atoms”

Yet, in the most typical use of natural gas today – in the energy industry – it is used as a source of heat/energy, that is it is broken down into even simpler components to release the energy contained in the chemical bonds.

Reacting with oxygen in the air it yields carbon dioxide (unwanted by-product), water (harmless by-product), and heat (desirable output):

CH4 + 2O2 => CO2 + 2H2O + Heat/Energy

Burning hydrocarbons drove the global economy in the last hundred years, but like the manuscript of the second part of Dead Souls that also produced some heat, alternative usage was/is possible.

Natural gas as a source of carbon

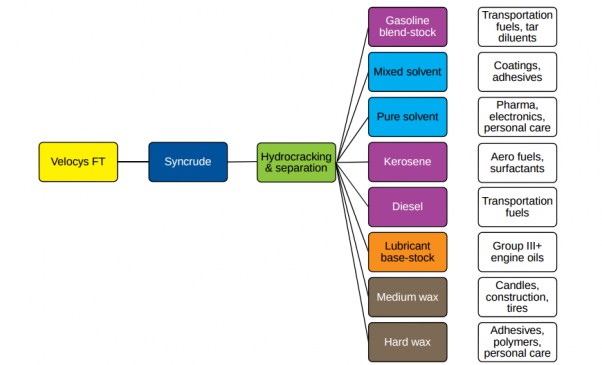

Chemistry based on CH4 is well known. It starts with straightforward transformation of methane into a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen (syngas), followed by almost a century old Fischer-Tropsch GTL (gas-to-liquids) process yielding a wide variety of output.

Source: Velocys

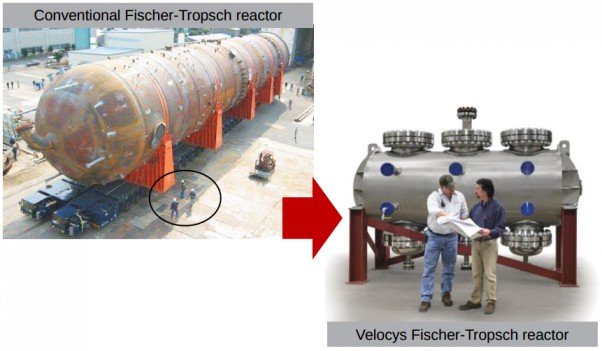

To be economic the technology required scale and has been put to work only at a handful of locations. A quintessence of centralised processing in the age of centralised production. Watch the scale!

Source: Shell’s Pearl GTL facility in Qatar

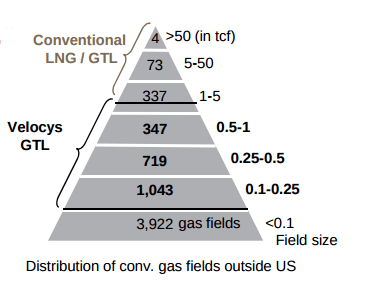

The problem though is that most natural gas in the world is distributed scale that can not be economically processed with conventional technology.

Source: Velocys

Distributed gas requires distributed processing facilities. The challenge on which the technology providers are starting to deliver.

Source: Velocys

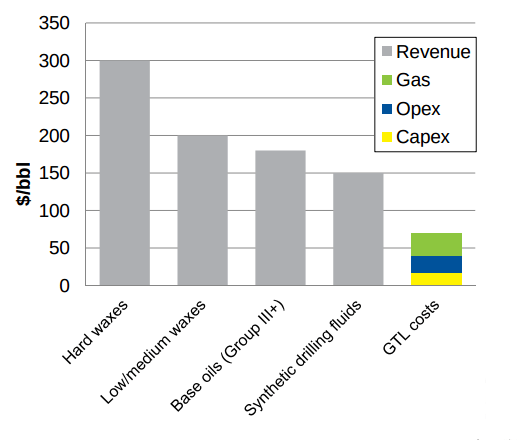

On the financial side, unlike large-scale GTL where new projects have been cancelled pre and post the recent oil price collapse (1, 2) due to costs escalation, technological advances enabling small-scale gas chemistry coupled with standardised modular approach to construction seem to provide reasonable economics, making alternative usage of gas (as a source of C) an interesting proposition.

Source: Velocys

Similar to the developments on the gas combustion side, gas-based chemistry is set to move towards distributed scale.

Natural gas: source of heat vs. source of carbon

There is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ usage of gas. Economics dictates the one, and so far the right one was combustion. One thing is clear though, burn it or transform it, in the future (for economic reasons) it is likely to be done on distributed scale via new enabling technology.

As centralised gas combustion (to generate electricity) is successfully challenged by solar/wind, I think we are not far from the times of natural gas glut (10 years?) when any alternative gas usage will receive extra attention. In case of natural gas the alternative (gas-based chemistry) is quite straightforward.

Wait, but natural gas is still a fossil fuel!

Natural gas won’t go anywhere just because it is a fossil fuel. It will only go when its economics becomes unfavorable relative to the alternatives (because we eventually ‘run out of gas’ and it becomes prohibitively expensive, or because of a technological breakthrough). Sustainable alternative to gas as an electricity feedstock is solar/wind (which is sorted), but what is the sustainable alternative to gas (and other hydrocarbons) as a source of carbon? The logical (if not the only) candidate is carbon dioxide in the atmosphere – the route that nature chose for herself.

In nature, plants and other organisms take carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, water, and sunlight, and convert it into complex organic compounds and oxygen through a process called photosynthesis:

n CO2 + n H2O + sunlight → (CH2O)n + n O2

Carbon dioxide Water Carbohydrates Oxygen

There are attempts to replicate this process (create artificial photosynthesis), and claims that the attempts have been successful:

Source: Joule

In the example above, the inputs are: waste carbon dioxide (source of C), non-potable water (source of H), sunlight (source of energy), catalysts, and genetically engineered micro-organisms (enabling the transformation). The inputs are abundant and distributed.

The technology claims to be economic (“stable supply and costs targeting $50-60 per barrel”), and able to produce a wide variety of output (“Each of our catalysts is engineered to convert CO2 to a specific molecule of interest”). I.e. it claims to challenge gas-based chemistry already today.

I don’t know if they succeed or some other technology innovator provides a better solution. Also, in the upcoming times of ‘gas glut’, there likely be a severe competition from traditional gas and gas-based chemistry.

One thing is certain though, traditional gas-based chemistry or artificial photosynthesis, it is going to be distributed scale.

Summary (gas)

Here is a summary of the developments on the gas side of the energy industry.

|

Gas for => |

Electricity |

Heat |

Carbon |

|

Scale |

Large, centralised |

Small, distributed |

Large => Small |

|

Challenged by |

Wind/solar |

Electricity |

Artificial photosynthesis |

|

Challenger competitive today? |

Yes |

No |

? |

|

Key developments |

Centralised gas combustion (for electricity) is not a going concern business model |

– Gas combustion (for heat) is very competitive – Utilisation of electricity by-product via enabling new technology |

Scale moves from large to small (whether it’s new gas-based chemistry or artificial photosynthesis) |