Oil is not Gas

In my previous writings on the developments in the energy industry I didn’t really make much of a difference between oil (used for transportation) and natural gas (used for electricity generation). Yet there is a significant one worth a separate investigation.

In electricity generation there is a clear alternative to conventional gas combustion. Wind electricity currently costs $0.04/kWh, solar electricity costs $0.06/kWh (and falling), and storage is to add only about $0.02-0.03/kWh. Not only being technologically feasible, solar and wind (complemented by storage) are economically preferred to the existing solutions based on fossil fuel combustion.

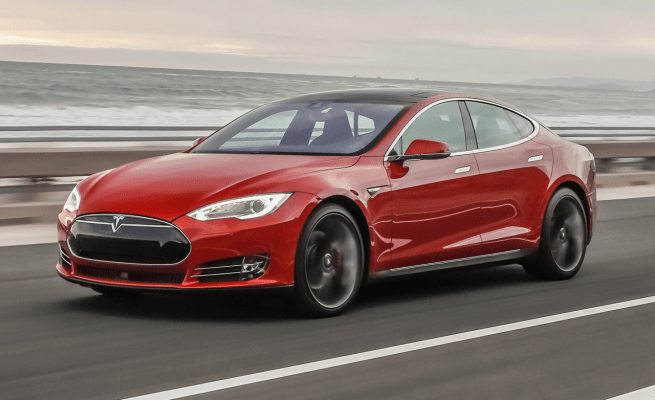

In transportation a clear alternative to gasoline/diesel vehicles is electric cars. But, unlike in electricity generation, electric cars while being technologically feasible are not economically competitive with traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) cars at the present moment. Tesla Model S may well be the best car ever produced, but it is an expensive one. While it saves the owner money (as it is much more economic to “fuel” a car with electricity rather than gasoline), the initial purchase price premium this car demands is not covered by the subsequent fuel savings.

An economic electric car, with adequate range, is yet to be demonstrated. But before it happened there already exists another solution that, on its own, and purely on economic grounds, can challenge conventional ICE vehicles as default choice in transportation (and significantly reduce demand for oil along the way).

PHEV

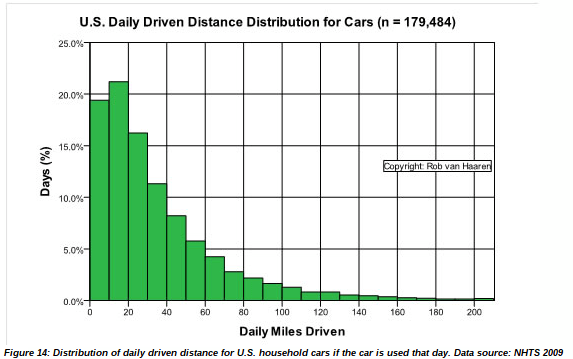

If we have a look at the analysis of the driving habits of a typical (american, in this instance) driver, we can find that most of the daily trips for most of the drivers are relatively short ones.

If you drive a typical ICE vehicle you don’t really care what this distribution looks like. But if you drive Tesla Model S you are upset as you know that the large battery that Model S carries (and that alone costs more than $20,000) is only used by a small fraction during most of the days (between your regular overnight rechargings). Large and expensive battery is the Tesla’s price for having comparable range with traditional ICE vehicles. But there are other solutions to match on the range.

PHEV approach combines a small battery (and electric motor) to cover short distances, and a traditional internal combustion engine to cover the long ones. In such a combination the engine plays a role similar to that of Tesla’s huge battery, serving when needed as a range extender. All three platforms (ICE, EV, PHEV) have their own economic pros and cons (as described in the table below) so a more detailed economic analysis is needed.

| Vehicle type: | Economic pros | Economic cons |

| Conventional (ICE) | No battery/el.motor needed | Expensive fuel, ICE add-on |

| Electric (EV) | Cheap “electricity” fuel, no ICE needed | Large battery/el.motor add-on |

| Hybrids (PHEV) | Cheap “electricity” fuel (mostly) | Small battery/el.motor add-on, ICE add-on |

Economic case for PHEV

PHEV-hybrids look like traditional vehicles and are often produced in pairs (with their classical counterparts).

Audi A3 (petrol) Audi A3 e-tron (PHEV-hybrid)

VW Golf GTI (petrol) VW Golf GTE (PHEV-hybrid)

Having such pairs around makes an apple to apple economic comparison easier. Let us have a look at traditional Audi A3 (petrol based) and compare it against its PHEV version Audi A3 e-tron:

- Purchase price (in the US) is higher for PHEV-version by $7,000. This is not surprising as PHEV carries additional battery and electric motor.

- What fuel economy does it produce? Based on the histogram above, an average US driver covers about 39 miles a day. Based on the same histogram, taking into account that Audi A3 e-tron’s battery capacity is 30 miles, the typical breakdown will be 24 miles covered from electricity and 15 miles from gasoline (see calculations here). Electricity cost would be 24 miles/3.5 miles per kwh*0.13$/kwh = $0.87, and petrol cost would be 15 miles/28 MPG*2.7$/gallon = $1.45, making the total 2.32$/day. Petrol-based A3 would cover the whole distance on gasoline at a cost of 3.76$/day. Thus, the total annual economy is about $525 (about 13 years payback).

13 years payback is not extraordinarily lucrative but over the economic life of the vehicle the owner is roughly indifferent, from the economic standpoint, between the petrol-car and the PHEV-hybrid.

In addition, a number of other things need to be taken into account:

- PHEV-hybrids as well as pure electric vehicles in many countries are eligible for special tax credits. These normally cover more than half of the PHEV premium. In the USA, for example, such credit would be between $4,000 and $7,500 depending on the size of the battery. With $4,000 the payback period reduces to less than 6 years. I am reluctant to call these credits “subsidies”. Electric vehicles and PHEV-hybrids are a more ecological transportation solution than a conventional ICE car. This is a structural advantage that is likely to have a permanent financial reflection in the form of a tax credit, a derivative of CO2-payments (if such payments are introduced), or in some other form.

- On the technology side, the batteries are getting cheaper, reducing the PHEV purchase price premium and the payback period. Even more promising, the engine technology is getting optimised to work best in tandem with electric powertrain. Such optimised engines would be lighter, more efficient, and as a result consume less liquid fuel.

- Payback period hugely depends on the regional characteristics. In fact, the US market is probably one of the least attractive from the PHEV economics standpoint: people in the US drive relatively much (which requires larger battery), and fuel prices are relatively low (that reduces the benefits of PHEV). In the UK, for example, where people drive on average ⅓ less, and fuel costs are more than twice that of the US, the annual economy would be more than $1,200 (see calculations here). This brings the payback period, after taking the local incentives into account, down to 1-2 years.

Thus, as it stands today, PHEV is a preferable option from the economic point of view for most of the drivers. And over time things will continue to improve further in favor of PHEV economics.

80/20 rule

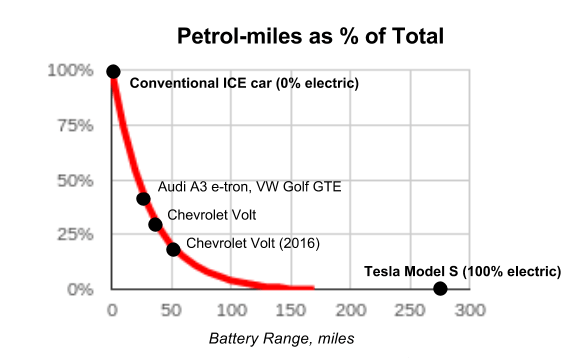

Different battery sizes imply different electricity / petrol breakdown. In fact, knowing the distribution of daily mileage, we can construct a typical breakdown for every possible battery size. (General dependence is shown below together with some of the existing PHEV models as they fit on the curve).

One of the intriguing features of this chart is that it takes about 20% of the Tesla Model S’ battery size, to provide for 80% petrol economy. The 80/20 rule in action.

Note that the fuel economy is not the desired outcome per se. We start with economic considerations and where it leads us, and get 80% fuel economy as a by-product. Putting economic rationale first is the most important characteristic feature of the ongoing developments in the energy space.

Is PHEV the direction the automotive industry is heading?

Yes. Here is two recent announcements typical of the ongoing developments in the automotive industry:

- Less than a year ago BMW announced that it will make PHEV versions of its every major model.

- Mercedes is following the steps planning to introduce 10 new PHEV models by 2017.

On the producer side the effort was launched rather by the regulators pushing for stricter environmental standards in the automotive industry. But on the consumer side this is the economics that is becoming the lead driver of the upcoming adoption.

Charging convenience

Daily (overnight) charging is a new routine characteristic of the upcoming PHEV / EV automotive age. Is it convenient? Less so than the status quo. But did the inconvenience of plugging-in your smartphone every night prevent you from adopting one? (Unless you are my mum the answer is likely to be No).

More so, the inconvenience is rather limited. Most PHEV producers are about to introduce wireless charging (including Audi, Ford, Toyota, etc) that doesn’t require any cords or actions. You just place your car on top of the wireless car charging station dock, leave the car, and when you return your car will be fully recharged. As they put it in Carmagazine, “any car calling itself a plug-in may need another monike”.

Also, many of the producers are working on the parking-assist systems that would help the driver to position the car in a parking spot for the wireless charging system to charge the car’s battery, making charging not only wireless but also mindless.

Implications for oil demand

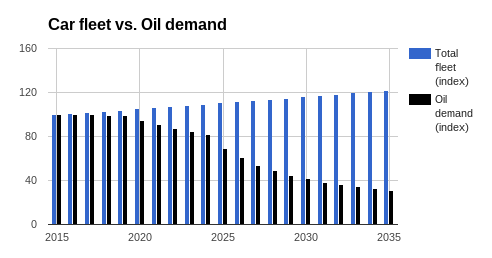

As we established there is one by-product of (economics-driven) PHEV adoption, namely structural reduction of the oil demand in transportation industry. While the exact trajectory is difficult to predict, schematically it should look as follows:

- 2015 (and before) – 2020: PHEV early adoption. Car producers improve technology / transfer model range to hybrid platform.

- 2020 – 2025: Aggressive adoption. By the end of this stage most of the new cars sold are PHEV/EV.

- 2025+: Displacement of accumulated ICE fleet.

With the 80/20 rule as it applies to hybrid vehicles the potential to reduce oil demand per vehicle is several fold making oil, after all, not that much different from natural gas.