This note is a follow up on the earlier note on the developments in the automotive industry, motivated by the recent scandal with Volkswagen emission violations.

Dieselgate

What happened (wiki):

“On 18 September 2015 the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a Notice of Violation to German automaker Volkswagen Group, after determining that the company had equipped vehicles with turbocharged direct injection (TDI) diesel engines with software programming that enabled their nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions controls only during laboratory emissions testing. This caused NOx emissions produced, and measured, during testing to be much lower than those produced during real-world driving – where the affected vehicles emitted up to 35 times the legal limit of NOx”.

The essence of what happened is best summarised here (EV Obsession):

“Dieselgate, very simply, was Volkswagen cheating the system to make its diesel cars pass emissions tests in the USA. But Volkswagen didn’t just do this out of a corporate drive to be evil. It did this because it couldn’t offer diesel cars in the USA that were both clean enough to comply with regulations and had the performance that buyers desired”.

In short (Elon Musk):

“What the Volkswagen [scandal] is really showing is that we’ve reached the limit of what is possible with diesel and gasoline”.

What it means for the auto industry: the most economic way to make a 50+ MPG car is to make a 150 MPG car.

Historically development of the diesel vehicles has been prompted by concerns about carbon dioxide emissions (diesel engines are better on CO2 than gasoline engines). More recently the air quality problem has moved up in the ranks making diesel vs. gasoline comparison less straightforward (diesel engines are worse on NOx and other pollutants).

Diesel or gasoline, the regulator’s approach has been to impose stricter emission limits gradually, hoping that squeezing 2-3% of extra performance every year will bring the industry where it needs to be over time. The new fleet is currently about 30 MPG (miles-per-gallon), so the regulator demands 50+ MPG by 2025 and monitors what actual technological progress brings.

The reality turned out to be different. The best way to satisfy the 50+ MPG requirement appeared to be not by incremental annual squeezes (to ultimately end up just above the required norm), but rather a step change to make a 150 MPG car (using a hybrid powertrain).

In a note on plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV) I argued that such vehicles make economic sense already today in the current price (for fuel / electricity / car) environment. At worst the premium paid for a modern PHEV returns to the buyer over the vehicle’s lifetime, at best – over just 1-2 years. (The note contrasted PHEV against gasoline cars, but the general conclusions still hold for PHEV-diesel comparison).

In the post-dieselgate world, premiums for PHEVs are likely to shrink further as traditional vehicles will probably incur extra costs, thus making PHEV economics even more compelling.

What it means for the petrochemical industry: “bottom up” gas chemistry vs. traditional “top down” oil refining.

Traditionally, diesel (gasoline, and other components) are derived from oil via refining process. A complex organic compound (which oil is) is split into simpler compounds, and much of the unwanted initial contents (nitrogen oxides, sulphur oxides, etc) ends up in those simpler compounds.

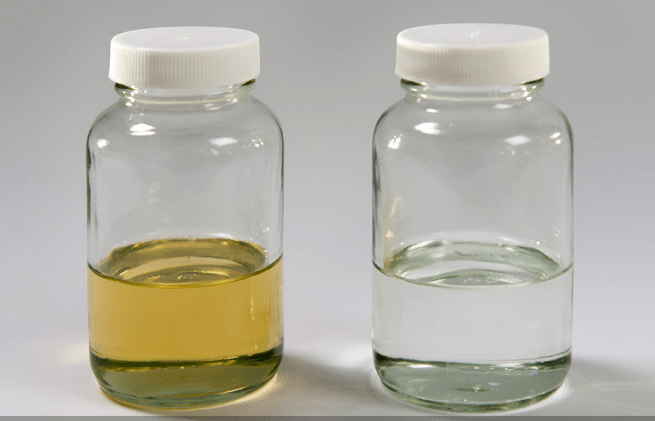

Another way to obtain diesel is to take a simple organic compound (like natural gas) and chemically upgrade the short hydrocarbon molecules to the desired length. As natural gas contains far lower amounts of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and sulphur oxides (SOx) compared to petroleum fuels, the product of such “build up” chemistry is also much cleaner (see picture below).

Synthetic diesel derived via gas-to-liquids technology (right) is cleaner than traditional diesel derived via oil refining (left) on SOx, NOx and particulates.

It is too early to expect any abrupt changes within petroleum industry but the recent events, in my view, will accelerate the ongoing transition from petroleum-fuel to electricity-fuel in transportation, and highlight natural gas “bottom up” chemistry as an alternative to traditional “top down” oil refining in petrochemistry.

P.S. Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)

As a side note, this is truly fascinating how the risks well articulated in the public domain (FT) can still cause evaporation of many billions of USD of market value at later stage:

“Research by the International Council on Clean Transportation, a non-profit group, last year (=2014) found that on-the-road NOx emissions from new diesel cars were on average seven times higher than EU legal limits”.