Is official GDP growth statistics an adequate measure of the impact the technology has had on the economy?

The effect of the technological progress of the late XX – early XXI centuries on our lives has been tremendous. At the same time, the official measures of the economic performance such as GDP growth statistics hardly notice any impact, and there are renewed talks of the prolonged sub-par economic growth (secular stagnation). How both phenomena are possible simultaneously? This note is an attempt to demonstrate how traditional GDP accounting fails to capture the true impact of technology on economic performance. In official numbers technology-driven deflation seems to be grossly underestimated, that results in seemingly subpar real GDP dynamics.

Productivity paradox

The productivity paradox – an apparent contradiction between the remarkable advances in technology and the relatively slow growth of productivity – has been recognised for a long time. Back in 1987, Robert Solow, a Nobel laureate in economics, observed that: “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics”. The academicians remain confused till today. In 2015, Lawrence Summers, a former Secretary of the US Treasury, noted: “There is a major puzzle regarding how technological changes, which seem to be associated with so much efficiency and certainly with job displacement, do not show up more visibly in productivity statistics”.

The productivity paradox has attracted a lot of attention because technology seemed no longer to be able to create the kind of productivity gains that occurred until the early 1970s.

Secular stagnation hypothesis reborn

Poor official GDP growth figures have recently resulted in the renewed interest to the notion of secular stagnation, a situation of the prolonged structural (as opposed to temporary and cyclical) sub-par economic growth.

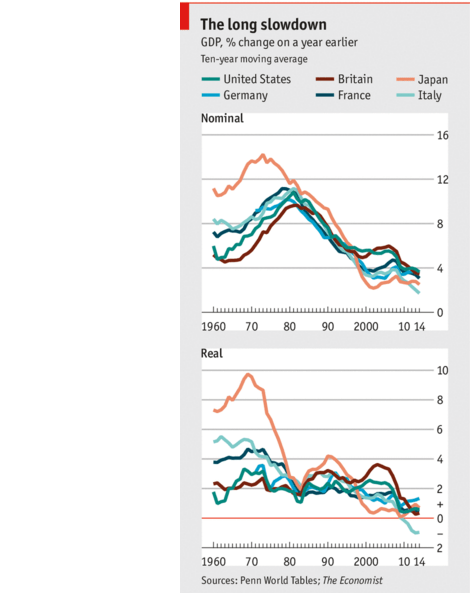

This is what the “secular stagnation” looks:

Source: The economist

There is a number of supporting arguments:

- The world is getting older. According to the OECD, the “demographic tax” imposed by global ageing will knock off 0.4% of global GDP growth in the next few years, rising to 0.9% by 2025.

- Debt expansion to compensate for weak demand is not an option in the overleveraged world.

- Aggressive monetary policies to promote robust economic growth across the globe have already been tried, and failed.

Overall, the argument is that the demand is weak, and the weakness is structural. But can these headwinds make the effects of the technological progress completely invisible?

The deflation argument

It’s not a new idea that there may be something wrong with the way the official GDP measurements capture technological progress. Erik Brynjolfsson, the person who popularised the productivity paradox, in 1993 asserted: “The sorts of benefits ascribed by managers to IT-increased quality, variety, customer service, speed and responsiveness – are precisely the aspects of output measurement that are poorly accounted for in productivity statistics as well as in most firms’ accounting numbers … The closer one examines the data behind the studies of IT performance, the more it looks like mismeasurement is at the core of the “productivity paradox”. Rapid innovation has made IT intensive industries particularly susceptible to the problems associated with measuring quality changes and valuing new products”.

This assertion is largely agreed on today: “There is plenty of room for debate about measurements of productivity. It is very likely that official statistics take insufficient account of quality improvements and new products” (Lawrence Summers).

But there is no consensus as for the reasons for inadequacy of standard GDP measures. One potential culprit is inappropriate accounting for deflation that was suggested by Erik Brynjolfsson himself: “When comparing two output levels, it is important to deflate the prices so they are in comparable “real” dollars. Accurate price adjustment should remove not only the effects of inflation but also adjust for any quality changes. Much of the measurement problem arises from the difficulty of developing accurate, quality-adjusted price deflators. Additional problems arise when new products or features are introduced”.

One of the nowadays proponents of the deflation argument is Marc Andreessen, an IT venture capitalist, who in his tweetstorm of late 2014 asserted: “While I am a bull on technological progress, it also seems that much of that progress is deflationary in nature, so even extremely rapid tech progress may not show up in GDP or productivity stats, even as it = higher real standards of living … In this world, we can have massive advances in real standards of living even w/formally low investment, GDP, & productivity growth”

And it didn’t take long for Lawrence Summers to disagree: “From an economist’s point of view, this paragraph is very hard to understand. Real GDP and productivity statistics are calculated after adjusting for price changes – so they are unaffected by inflation or deflation … But I at least cannot understand in what sense this phenomenon (VK: technological changes not showing up more visibly in productivity statistics) can be attributed to technological progress’ deflationary character”.

Let’s see how it can.

How technology-driven deflation works, and miscalculated

Assume you produce GPS navigators (on a picture below). Assume that production volumes are flat, but the price drops from 400$ to 300$ per unit. What will be the effect captured by GDP accounting? GDP deflator (in this industry) would be measured as -25%, and impact on real GDP would be zero (as volumes are unchanged). Price effect (deflation) is perfectly separated from the real effect.

But what happens in reality is that 400$ GPS devices are being replaced by 300$ smartphones (on a picture below). Official GDP accounting naturally treats the two (GPS navigators, and Smartphones) as different industries, and records -400$ impact on GDP on GPS navigator side, and +300$ impact on Smartphone side, per each replacement. Net impact on GDP, as per standard macroeconomic accounting, is -100$.

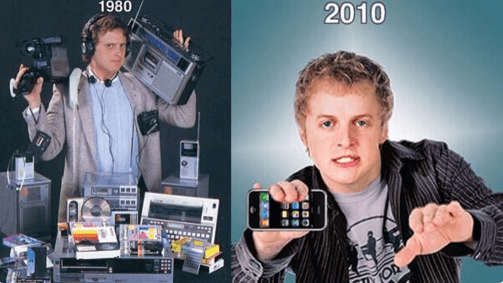

The total replacement has been colossal:

“Your smartphone is the new Swiss Army Knife” (Source: Makeuseof)

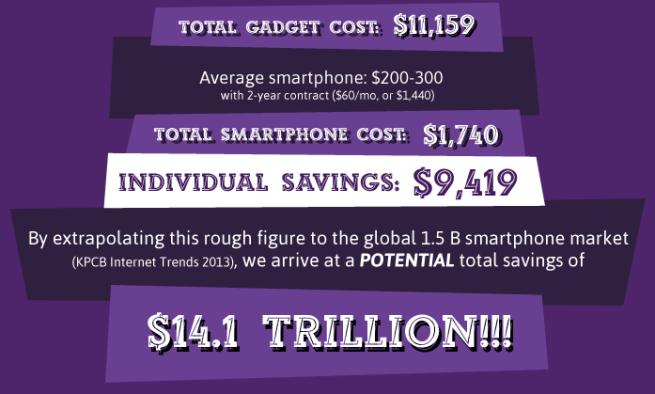

Thousands dollars worth of stuff is being replaced by hundreds dollars worth smartphones. The thousands lost (adjusted for the hundreds gained) are recorded as net negative impact on real(!) GDP, and deflation is assumed negligible. Why is that? Because GDP accountants don’t treat a single product on the right side of the picture above, as continuation of the product lines on the left. If they did, and to me it looks logically right, the reported deflation would be tremendous, and the real GDP would be much higher. How much higher?

The spirit of GDP accounting is to calculate the various stuff produced at constant prices (which makes it possible to interpret the total aggregate as a real quantity). On a 1.5 billion units smartphone market, with each smartphone “worth” of 10,000$ of replaced gadgets, the total “value added” is about 15trl$/year in yesterday’s dollars. This is about 20% of global GDP, which means that over the past decade of smartphone proliferation we might have been underestimating global GDP growth by at least 2%/year, which immediately moves the past decade from the “below trend growth” category, to the “above trend growth”. No paradox in the end: accelerated technological progress, accompanied by above average GDP growth.

Source: eBay

Remember several decades ago, a few supercomputers worth millions of dollars each, belonged only to the likes of NASA and the Pentagon. Today, devices with the same capabilities – smartphones – belong to everyone’s pocket. But official GDP statistics does not take the latter product line as continuation of the former. Smartphones are considered a new product with a starting price (for the purposes of macroeconomic accounting) of a few hundreds of dollars. As a result, with standard GDP accounting procedures deflation turns out to be significantly underestimated, as well as the real economic growth. Technology-driven deflation, which should be accounted as a monetary phenomenon, in official statistics impacts the real side of GDP. If tomorrow, some “sHmartphone” device is invented worth tens of dollars as opposed to hundreds, in official numbers we again see a huge negative impact on smartphone market (and real side of GDP)..

Implications

- If deflation is grossly underestimated, the real purchasing power of the currency is underestimated either.

- Seemingly missing, technology-driven productivity gains manifest themselves through deflation and rising purchasing power of the currency.

- Blaming weak demand has been equally wrong. Nominal demand growth may indeed be weak compared to historical trends, but proper adjustment for deflation makes real demand look much better, and probably above the historical trends.

- Nominal interest rates, currently at about historical lows, are not that low in real terms once you properly take deflation into account. With actual real rates higher than implied by the official inflation, nominal rates may stay lower for longer.

We seem to be interested on same topic, i.e. Technological Deflation. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/moores-law3-tatu-lund

LikeLiked by 1 person