In a recent article The Economist explores the reasons for extraordinarily high profitability in the corporate America and concludes that it is due to rising monopolisation of America Inc. This note provides an alternative explanation. Post-industrial capitalism of the XXI century is featuring a shift from capital, as the key production factor, to knowledge. Establishment of the new economic model is characterised by rapid advances in technology leading to digitalization and robotisation of the manufacturing process, Moore’s law-driven structural deflation, and low capital intensity of the marginal growth. An ongoing shift from the capital-dominated economy to the knowledge-dominated economy leaves exactly the same traces that would be seen if monopolisation was indeed intensifying.

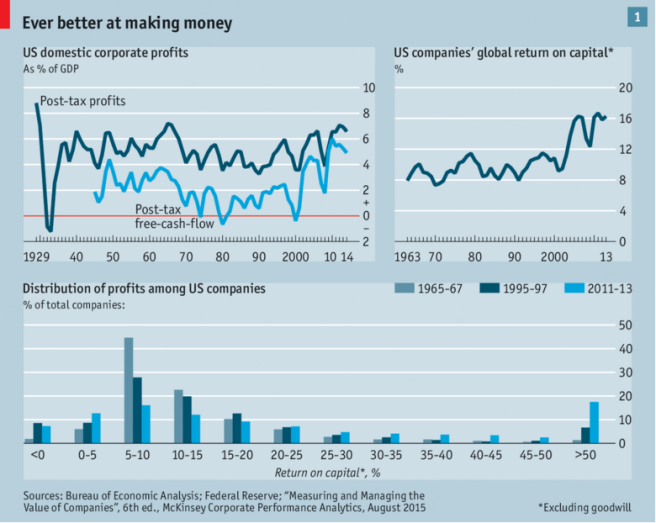

US corporate profits as proportion of GDP (top left on the chart) are at very high levels. The mirror image of that is lower revenue share going to workers driven by internationalisation of the labour force (lower wages elsewhere), and robotisation of the manufacturing process (no wages at all).

Capital intensity of the marginal growth is very low. Take a look at Google – one of the champions of the new economy. Google’s tangible assets are less than 40bn$ whereas its market value that reflects its earnings power is more than 500bn$, i.e. less than 10% of the market value is due to actual capital on the balance sheet. Low capital intensity leads to lower capital expenditures and higher free cash flows (light blue line on the chart).

Return on capital in this situation (top right) is high not because ‘return’ is excessive, but because less ‘capital’ is needed. With low denominator the profitability ratio becomes unusually high.

Distribution of profits (bottom of the chart) shows few worrying signs. The largest shifts have been a significant reduction in the proportion of companies generating 5-10% return on capital, and significant increase of those generating more than 50%. Both add to the overall profitability of the corporate America, but neither has anything to do with alleged monopolisation. The companies in the 5-10% bracket generate below their cost of capital, reduction in this category is a sign of normalisation, not monopolisation. And the companies with 50%+ return on capital are low capital intensity googles and facebooks of the emerging knowledge economy.

Is Google a monopoly? Yes, in the sense that it dominates its market. But no, in the sense that it is not “more adept at siphoning wealth off than creating it afresh”. A classical monopolistic behaviour is the one where a firm raises prices which results in lower output but higher profits. This is not what Google does. Google’s primary source of income is contextual advertising, where it runs competitive auctions to set the prices. Nothing like raising the prices beyond the justified levels.

Finally, the question of high earnings persistency. The Economist argues, in the classical tradition, that if we lived in the competitive environment high return on capital would attract new competition and normalise profitability over time. In today’s world it does not happen though.

Classically, the price of any product or service is composed of the cost of labour and the cost of capital. Once a company incorporates too high cost of capital into the price, a competitor arrives, replicates the business model, demands lower cost of capital, and thus able to lower the price and win the market share. But this logic fails if the price in the first place is set by the market, like at Google AdWords’ price auctions. Potential competitors can replicate the business model at reasonable cost, but they can not change pricing as this would be like selling a barrel of oil at half the market price.

Digital is one of the most competitive sectors in the economy, and yet naturally very profitable. The successful enterprises in the digital economy are global scale, generate high revenues, and given low capital intensity demonstrate high return on capital.

The sectors where you would search for real signs of monopolisation are the traditional high capital intensity industries like automotive or space. And yet what happens is the disruptions like Tesla and SpaceX. Who would think 10 years ago that space – a traditional oligopolistic state controlled sector operating under cost plus regime – would be disrupted in such a remarkable way by a recent startup?

We have explained all the evidence without resorting to monopolisation. Moreover, as the emerging knowledge economy continues spreading around the highlighted deviations from the past trends will only get more pronounced. The importance of physical labor and its share of revenue will continue to diminish, as well as the importance of physical capital, whereas knowledge and technology will advance as the primary production factors. ‘Share of capital’ will continue to increase as it incorporates the shares attributable to both ‘tangible capital’ and ‘knowledge and technology’ (the equity providers own both). The former will slide, but the latter will skyrocket. Finally, return on tangible capital will keep rising as the denominator will continue decreasing. Thus, while monopolisation scenario provides a plausible explanation of the evidence within the traditional tangible capital dominated economy framework, the new knowledge economy does not require it.

The old economy and the new economy coexist today, and depending on the perspective one can see different pictures. The traditional view culminates in revival of the notion of secular stagnation that apparently bodes well with the monopolisation possibility. The picture one can see is that of Larry Summers: “If monopoly power increased, one would expect to see higher profits, lower investment as firms restricted output, and lower interest rates as the demand for capital was reduced. This is exactly what we have seen in recent years! … Only the monopoly-power story can convincingly account for the divergence between the profit rate and the behavior of real interest rates and investment”. From the new economy perspective one can see a creative destruction type of changes ongoing, putting some pressure on the traditional economy in the meanwhile, but leading to the ultimate good as all the technology driven transformations have been in the past.