The original note was published in Russian as “Зачем капитал экономике знаний” in Vedomosti on 26 April 2016.

***

On March 10th the European central bank announced a new round of monetary policy easing. The regulator lowered the interest rate – the traditional instrument to manage the money supply, and also increased the size of the quantitative easing program – the mechanism enabling money supply growth beyond the levels demanded in the zero interest rate environment.

It is traditionally believed that capital availability should stimulate credit growth and increase investments in the productive assets, which in turn should resolve the outstanding problems of the Eurozone: high unemployment, risk of deflation, and slow economic growth.

However, the monetary policy tools elaborated in the XX century may not be suitable for the realities of the XXI. From the industrial revolution of the XVIII century until recently the key production factor in the economy has been physical capital. Hence, monetary policy targeted steady growth in the productive capital base and its full utilisation. In the XXI century the key production factor becomes knowledge. The leaders of the new economy – Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and alike – grow faster than the economy on average not because the cost of credit has become a few basis points cheaper. In fact the cost of credit for such companies is not important at all, as capital intensity of the business model of each of these companies is very low.

Like the generals who prepare for the last war, the monetary authorities today use the instruments suitable for the industrial capitalism of the past. Below we will investigate who the visible symptoms (unemployment, deflation, and stagnation) can be interpreted differently within the old and the new paradigms.

Unemployment

Within the paradigm of the industrial capitalism of the XX century high unemployment is a sign of deficiency of the machines. To fight such unemployment you need to provide more credit to a machine-producing company, thus giving a job to both people who will be building the new machines and those who will be operating them.

Also within the traditional paradigm, high unemployment can be a result of lack of demand for the output of a worker operating the machine. This typically happens after the economic and financial crises when consumers become excessively prudent giving rise to the paradox of thrift. In such cases to get the worker back to the machine you need to stimulate demand via the countercyclical keynesian methods of fiscal policy.

These traditional methods are ineffective to solve the unemployment problem in the knowledge economy. In such an economy there is no need to have a worker operating the machine. This is just too expensive.

How much does the human labour cost? Just the physical part of it, not the complex output of the human activity. A healthy person can produce no more than 500 watts of power during several hours (this figure is correct for a professional athlete, e.g. a professional cyclist covering a few hundred kilometers during the ride). With a 40-hour workweek and electricity price of 0.2USD/kilowatt-hour, the money equivalent of physical labor cost is about 18USD per month. This is very cheap compared to total labor costs in most of the world.

Once modern technology replicates a function traditionally performed by humans in a given domain, i.e. the technology effectively enables segregation of the cheap physical labour component, human labour becomes obsolete in that domain. Robotisation of the production process is an ongoing development whose potential is far from being fully realised.

Unemployment in the new knowledge economy is structural. Solution to this problem lies in the field of education policy (training and retraining workers to gain new skills) and social policy (redistribution of income towards those not able to retrain), but not in the field of monetary policy.

Deflation

The hazards of deflation are known since the Great Depression of 1929-1933. Deflation (lower prices) leads to lower revenues for the corporations, in the situation when these corporations’ liabilities are fixed in nominal terms. This results in higher real cost of debt and further slowdown in economic activity.

However, as we discussed above, the importance of capital as a production factor in the emerging knowledge economy is less than that in the industrial economy, and so the risk of higher, deflation led, real cost of capital should not be overestimated.

Even more important is the observation that traditional macroeconomic statistics seems to miscalculate deflation. Assume there is a GPS navigation device that sells for 400USD apiece on the market. In a year’s time the price falls to 300USD, market size remains unchanged. What will the official statistics show? Real growth of 0% and deflation of -25%, which would be an accurate description of reality. In real life though the consumers don’t buy GPS devices anymore. In place of a single function navigator that used to sell for 400USD they buy multifunctional smartphones (with embedded GPS navigation function) for 300USD.

Official macroeconomic statistics treats the market for GPS devices and the smartphone market as two different markets. The statistics would show a decline of -400USD on the former, and a rise of +300USD on the latter. The net effect would be a “decline” of 100USD, or -25%, in real GDP. Thus, a purely monetary phenomenon (price decline for a navigation service that is now incorporated in a multifunctional device) would be shown as a negative real effect on GDP in the official statistics. The list of devices replaced by modern smartphones is long, implying that the official GDP deflator is significantly overestimated and hence the official real GDP growth is significantly underestimated.

Source: Makeuseof

Deflation in the XXI century is a technological phenomenon, not monetary. Deflationary environment for the likes of Apple and Samsung is nothing but natural, and has nothing to do with a century old deflationary spiral. The attempts to fight technological deflation with traditional monetary policy tools will not give the desired outcome.

Stagnation

“Slow” economic growth stops looking slow if we properly account for deflation.

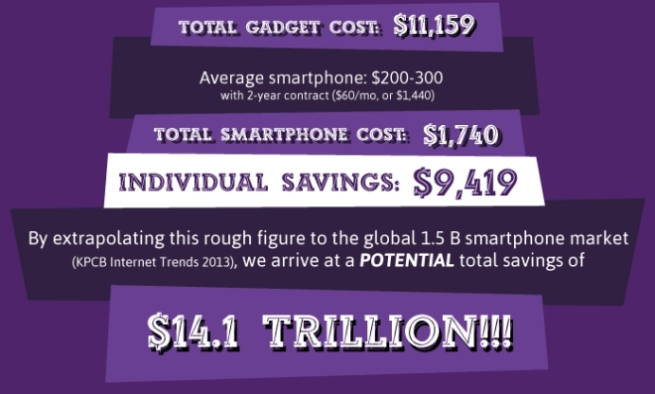

The smartphone market is about 1.5 billion devices a year. Each smartphone, by some estimates, replaces around 10,000USD worth of gadgets of the past. Thus, in constant, pre-deflationary prices this market is worth 15 trillion USD a year, or about 20% of the global GDP. Assuming that this value has been formed over the past 10 years, the official statistics underestimated global GDP growth by 1.5 trillion USD a year over the past decade, or about 2% a year. This adjustment makes the past decade one of the most successful ones in economic history.

Source: Adweek

***

Knowledge economy is the model coming to replace industrial and postindustrial capitalism in the developed world. Importance of capital as a production factor, the cost of capital, and hence importance of the monetary policy in the new economy moves to the back, whereas importance of knowledge and technologies comes to the front.

Transition to the new economy doesn’t happen evenly for all groups of people, which is reflected in such macroeconomic indicators as unemployment. Other standard macroeconomic indicators – inflation and economic growth – happen to be inadequate to reflect improving quality of life accompanying the establishment of the new economy.

If monetary policy has a lesser impact on development of the real sector of the economy, what does it have an impact on? First, the financial system itself – the banks and financial institutions whose business models are built around the interest rate differential. This is an unusual situation as financial sector is only important to the economy through its interaction with the real sector.

Another possible consequence of the ultraeasy monetary policy is increasing consumer spending beyond the normalised levels stimulated by cheap consumer credit. Growing consumer spending has a positive impact on the real economy, but average across a cycle such effect is neutral at best: after the binge comes the crisis and then the hangover. The last consumer binge ended in 2008 which is, probably, not too long ago to expect development of a new consumer spending cycle.

They say you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink. European and american monetary authorities during the last several years try hard to lead their economies to the source of cheap liquidity. But may be the technological horse doesn’t need water?